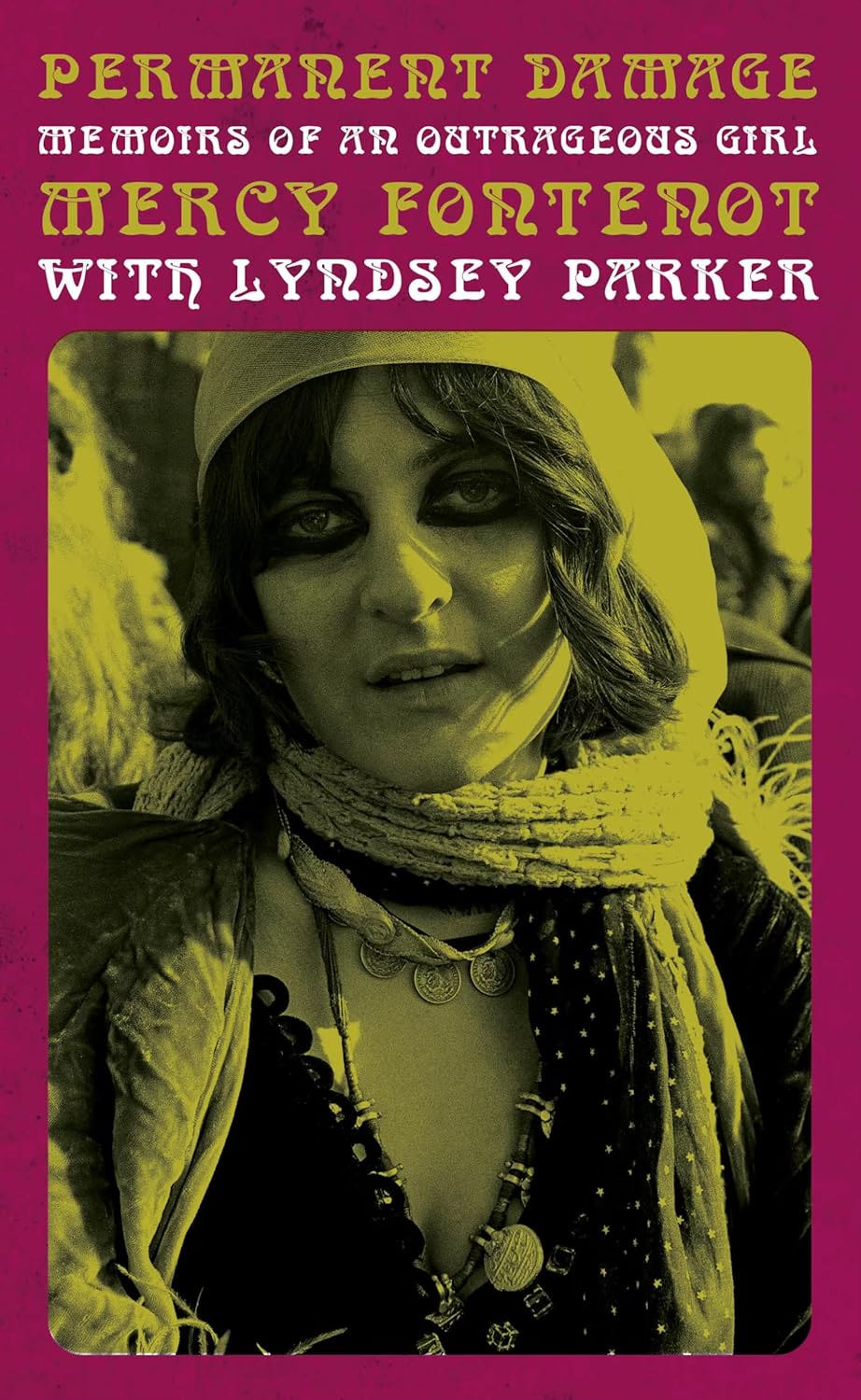

Q+A: Lyndsey Parker on Writing a 'Stranger Than Fiction' Memoir with Mercy Fontenot

Interview with an LA Woman!

Lyndsey Parker convinced the late Mercy Fontenot to tell her incredible life story in Permanent Damage: Memoirs of an Outrageous Girl. But, as she tells us in this week’s compelling Q+A, it wasn’t easy!

Tamara Palmer/Music Book Club: You recently told me that writing this book was the hardest thing you've ever done. Can you talk about the years-long journey of convincing Miss Mercy that she should share her incredible life story, and what the difficulties were once she agreed to do it?

Lyndsey Parker: I first met Mercy through Pamela Des Barres, her bandmate in the GTOs and longtime dearest friend. Pamela famously throws backyard parties at her “hippie pad,” and Mercy would always be there, holding court, wearing something garish and red and featuring at least three different clashing patterns of leopard print. She was hard to miss, but she was intimidating and I never approached her. One day at a Pamela party around 2014, she yelled something across the living room about seeing me on TV (doing music commentary on the local news), and said, “You’re really smart!”

Mercy was the type of woman to let you know exactly where you stood with her -- she either liked you or she didn’t, and if she liked you, she liked you a LOT. For some reason, she took an immediate shine to me. That was how our friendship formed, and for the next three years, whenever she would randomly blather on about doing crack with ex-boyfriend Arthur Lee or hanging out at Robert Stigwood’s mansion with Jobriath or jumping out of a cake at Alice Cooper’s record release party while on PCP or getting her rent paid by Michael Hutchence -- all stuff in the book, by the way -- I would tell she needed to write her own autobiography. She would always dismiss the idea, but then the next time I saw her she’d randomly mention being in Jimi Hendrix’s movie Rainbow Bridge or her fling with Al Green or some other crazy story, and I would nag her again.

Fast-forward to February 2017, and after she had a health scare (related to her cancer, which sadly eventually got her in 2020), she invited me to her birthday dinner at a Mexican restaurant. After too many margaritas, I volunteered, in front of a table of witnesses, to help her write her autobiography. The next day, probably feeling a sense of her own mortality, she called me up and said, “So, are we doing this book or what?” And that was that. When Mercy made her mind up about something, nothing would stop her. The next weekend she came over to my place, I gave her a Monster Energy drink and practically poured it down her throat, I turned on my audio recorder, and we talked for about four hours about her life. We did that again and again, two or three times a week, over probably the next two years.

I think I have at least 60 hours of recorded conversations with Mercy. Maybe one day I’ll listen to them again, but I think hearing her voice again would be a bit jolting. This may sound strange, since Mercy and I spent so much time together, but she has been gone for more than five years now, and I’ve spent so much time finishing the book, finding photos for the book, and doing interviews and promoting the book in the years since, that sometimes she almost feels like a fictional character I made up. But I assure you, she was very, very real. Mercy’s life was stranger than fiction, and much more interesting.

What was your process like when writing this book, and how long did it take to put together?

Sometimes I realize with a chuckle that I kind of did everything “wrong” when it came to this book. We wrote it without a book deal. The book was about 80 percent finished before we even pursued a deal, and I never even wrote a book proposal. And the book came out after Mercy died, which also wasn’t the plan, of course. Also, Mercy and I didn’t have a typical biographer/subject relationship at all. Obviously, we were friends first. I don’t think this book would have gotten done any other way. She needed to trust her writing partner, and frankly, she needed a writing partner who cared enough about her and was patient enough to stick with her, because yeah, this was NOT easy.

The process was Mercy and I would meet somewhere, like my home or a coffee shop or a restaurant, and I would interview her. I figured I would do this chronologically, starting with questions about her childhood, then her Haight-Ashbury years, then the GTOs years, then the Shuggie Otis marriage, then her punk years, and so on. But that is not how Mercy’s brain works! Nothing was linear. We’d be talking about something that happened in 1967, and then suddenly she’d go off on a tangent and I’d realize she had jumped to an incident from 1998, and there was no way I could steer the conversation back to ‘67. So, I just let her talk, and talk, and talk, and I’d see where the conversation took us and figured I’d make sense of it all later.

Sometimes it took multiple conversations to cover certain incidents, either because all the drugs she’d taken had clouded her recollection, or because some memories were too painful for her to revisit (although she’d rarely admit to this), or both. But every time I spoke with her, even when I thought I certain subjects were well-covered, I learned something new. I even got in the habit of carrying my little “note-to-self”-style audio recorder with me whenever she and I hung out socially, just in case she suddenly started sharing some story or detail I hadn’t heard before. I was always whipping out that thing and sticking it in her face.

After two years, 60-plus hours of conversation, and hundreds of pages of transcription, I finally retreated to a cabin in the woods and began trying to organize Mercy’s thoughts. It took me literally two weeks, which was a lot longer than I’d thought, just to parse out chunks of conversation into separate Word docs labeled “Punk Scene” or “Memphis” or “Homeless Years,” etc. After that, the words -- all of Mercy’s words, very much in her own voice -- began to take slowly shape into some sort of narrative, even if that narrative still went off on the occasional Mercy-style tangent. I recall someone on Instagram by the handle @garbanzopaws later described reading Permanent Damage as feeling like “your hippie mom’s most edgy friend ever is spending the night on your couch keeping up till sunrise with her horrifying stories of rock debauchery and now you’ll never be the same,” and I realized I’d gotten it right!

It was also very important for me to get the right tone. Let’s face it, Mercy had a hard life, and she went through some dark times. She endured a chaotic childhood, multiple sexual assaults, domestic abuse, body-image issues, and years of homelessness, and she took elephant-tranquilizing levels of every drug imaginable. And those hard, dark times were actually some of her most interesting stories, much more so than the typical rock ‘n’ roll escapades, so they needed to be in there. But Mercy had very few regrets, she thought her life had been “fun” (yes, that was her description!), and she didn’t ever feel sorry for herself -- so she would have been aghast if she thought anyone would pity her after reading her life story. So, finding the right balance between her “fun” tales and the not-so-fun-but-fascinating ones was a real challenge. MOJO did later describe the book as “very dark,” but there was no way getting around that -- and it was a four-star review, so I think Mercy would have been OK with that.

The other big challenge was making Mercy likable. The woman had a heart of gold, I swear, but it was surrounded by armor and hard for even me to penetrate. And she had a blunt, rough way of speaking that translated to the written word and could make her seem cold. I recall, after she had died and I was finishing the book, that a writer friend of mine who I’d given the draft to for feedback had honestly told me that he found Mercy’s story interesting and well-written, but he didn’t empathize with her or root for her. This was a problem! He said this was mostly because of her fraught and often estranged relationship with her son.

Then, by some miracle, when I was hunting down photos and looking through some of Mercy’s personal effects I’d inherited, I found a diary she’d written in the ‘90s. Mind you, she’d told me repeatedly when I asked if she’d ever kept journals (which obviously would have been hugely helpful) that she’d only done that in the ‘70s, and that her then-husband Shuggie Otis had ripped them all up in a jealous rage. But here were her own words, written much later in life after she got sober, where she was very candid about her love for her son Lucky and her desire to make things right with him. I took a photo of one of the diary’s pages and texted it to my writer friend, who texted back, “YES! That’s what missing! There you go.” There you go, indeed. Many of that diary’s words went right into the new and final draft, verbatim. That’s when I knew the book was ready.

Do you think platonic relationships were more important than sexual ones to Miss Mercy?

Absolutely. Mercy was not really a “groupie” -- although she would always get that tag because of her close association with Pamela Des Barres, who wears that tag with pride, and she didn’t mind the advantages that came with that tag. It meant she’d be included in VH1 specials and documentaries and anthologies about groupie lore. But Mercy was not sexually driven, at all. She didn’t even really like sex, and she sometimes wondered if she was actually gay. (She did have some crushes on women, although she only occasionally acted on such feelings.)

I have said that while the craziest, most headline-grabbing stories in Pamela’s I’m With the Band were the sexual encounters, Mercy’s craziest stories were mostly about drugs. Lots and lots of drugs. That was why when Mercy suggested that her autobiography be called Jukebox Jezebel, or even worse, I’m With the Band Too, I shut that down immediately. Neither were accurate. To be honest, I don’t even like that quote that keeps getting used because Mercy said it in Rolling Stone once, when she called herself “the Mae West of 1968” (mostly because she was fuller-figured compared to the other waifish GTOs). That’s not accurate either. Mercy was “the Mercy Fontenot of 1968,” not some sexpot bombshell.

Really, for Mercy it was all about the music and the drugs. She seemed to have insatiable appetites for both. And while she knew the drug adventures would make the book more sensational, in the end what she really wanted to be known and respected for was her vast wealth of musical knowledge. She had great taste, an uncanny Zelig-like ability to seek out what he called “energy centers” (whether it was San Francisco and Memphis in the ‘60s or the Hollywood punk scene in the late ‘70s), and there was nothing she enjoyed more than talking music with Frank Zappa or Johnny Otis and holding her own. She considered herself a musical historian, and I have always said she should have gone into A&R.

So, yes, this is my very long-winded way of me answering your question and saying that Mercy’s platonic friendships with musicians (Gram Parsons, Jobriath, Frank Zappa, Jeff Beck, Marianne Faithfull, Rod Stewart, Alice Cooper) meant much more to her than anyone she went to bed with. I think the fact that famous friends like Alice Cooper, Dave Davies, Exene Cervenka, Blackbyrd McKnight, and Shirley Manson all contributed blubs for the Permanent Damage book jacket calling her “the real deal,” a “one-off iconoclast,” a “counterculture cover girl,” and a “rock ‘’n roll rebel to end” is exactly how she’d want to be remembered.

This book is a testament to your strong skills as an interviewer! You've interviewed (and continue to interview) so many musical luminaries as well. Do you have any advice for conducting interviews that put your subject at ease and allow them to open up to you?

Aw, thank you! That means a lot. I am not exactly sure how I put someone at ease -- I mean, there’s the obvious, presumably common-sense stuff about gently easing into any tough or touchy subjects, reading body language and facial expressions, etc. I guess my main advice would be to come to an interview very prepared, of course, but be willing to veer from your “script.” Don’t just have your questions and ask them in order 1, 2, 3. Listen. Some of my best interviews turned out totally different from what I expected, because the subject went off on -- you guessed it! -- a tangent when I listened and asked follow-up questions. It's just important to be curious, and asking curious, seeking questions. Sometimes the story you think you’re going to get, going into an interview, isn’t as interesting as the one you end up actually getting. That definitely was the case with Mercy.

Are you or would you like to be working on more books?

The idea daunts me a bit, to be honest, since the Mercy process was four years of my life and also a very unique experience I don’t think I’ll ever be able to replicate. But… yes. I have a list on the Notes app on my phone of people whose stories I’d like to help tell, and maybe one day my years of nagging Toni Basil will finally pay off. She’s my number one. I also have an idea for a non-fiction coffee-table book about a certain local scene that few people know about. But I think I’ll know when I’ve encountered the right subject again.

Could you recommend any favorite music books (current or classic) to us?

My favorite autobiographies or biographies (besides I’m With the Band, of course!) are Love Is a Mixtape and Talking to Girls About Duran Duran by Rob Sheffield (he makes me so jealous; I wish I could write like him), Clothes Clothes Clothes Music Music Music Boys Boys Boys by Viv Albertine, Hollywood Park by Mikel Jollett, Earth to Moon by Moon Zappa, Everything I Ever Wanted by Kathy Valentine, Just Kids by Patti Smith, So You Wanna Be a Rock & Roll Star by Jacob Slichter, Crazy From the Heat by David Lee Roth, Without You: The Tragic Story of Badfinger by Dan Matovina, Cured: The Tale of Two Imaginary Boys by Lol Tolhurst, Wild Boy: My Life in Duran Duran by Andy Taylor, Lonely Boy: Tales From a Sexy Pistol by Steve Jones, Take It Like a Man by Boy George, Tranny by Laura Jane Grace, Neon Angel by Cherie Currie, Scar Tissue by Anthony Kiedis, Memoirs of an Imperfect Angel by Mariah Carey, all of John Lydon and Peter Hook’s memoirs, and absolutely, the juiciest and craziest autobiography that never gets old, Motley Crue’s The Dirt.

The anthologies and oral histories Nothin’ But a Good Time (by Tom Beaujour & Richard Bienstock), I Want My MTV (by Rob Tannenbaum & Craig Marks), Rip It Up and Start Again and Shock and Awe: Glam Rock and Its Legacy (both by Simon Reynolds), and They Just Seem a Little Weird: How KISS, Cheap Trick, Aerosmith, and Starz Remade Rock ‘n’ Roll (by Doug Brod) are also awesome. Is that long enough a list for you? I am sure I’m forgetting a bunch. All I really read are music books. I’m currently reading Peter Doherty and Bobby Gillespie’s autobiographies at the same time. Just making this list actually has me wanting to get started on writing another book myself…

Previously in our Q+A series:

Christina Ward on Running Feral House, a 36-Year-Old Indie Book Company

Ali Smith on Speedball Baby and Telling Stories Without Shame

Arusa Qureshi on Her Love Letter to Women in UK Hip-Hop

Lily Moayeri on Her Favorite Music Books and Writing from a Personal Place

Megan Volpert on Why Alanis Morissette Matters and Writing 15 Books in 18 Years

Mark Swartz on Biggie + Yoko Ono as a Crime-Fighting Duo and Other Fictional Ideas

Annie Zaleski on Cher, Stevie Nicks and Pushing Past Writing Fears

Nelson George on His Next Book and Making Mixtapes in Paper Form

Michaelangelo Matos on Writing and Editing Music Books

Yay!! So glad you did this Q+A with Lyndsey!