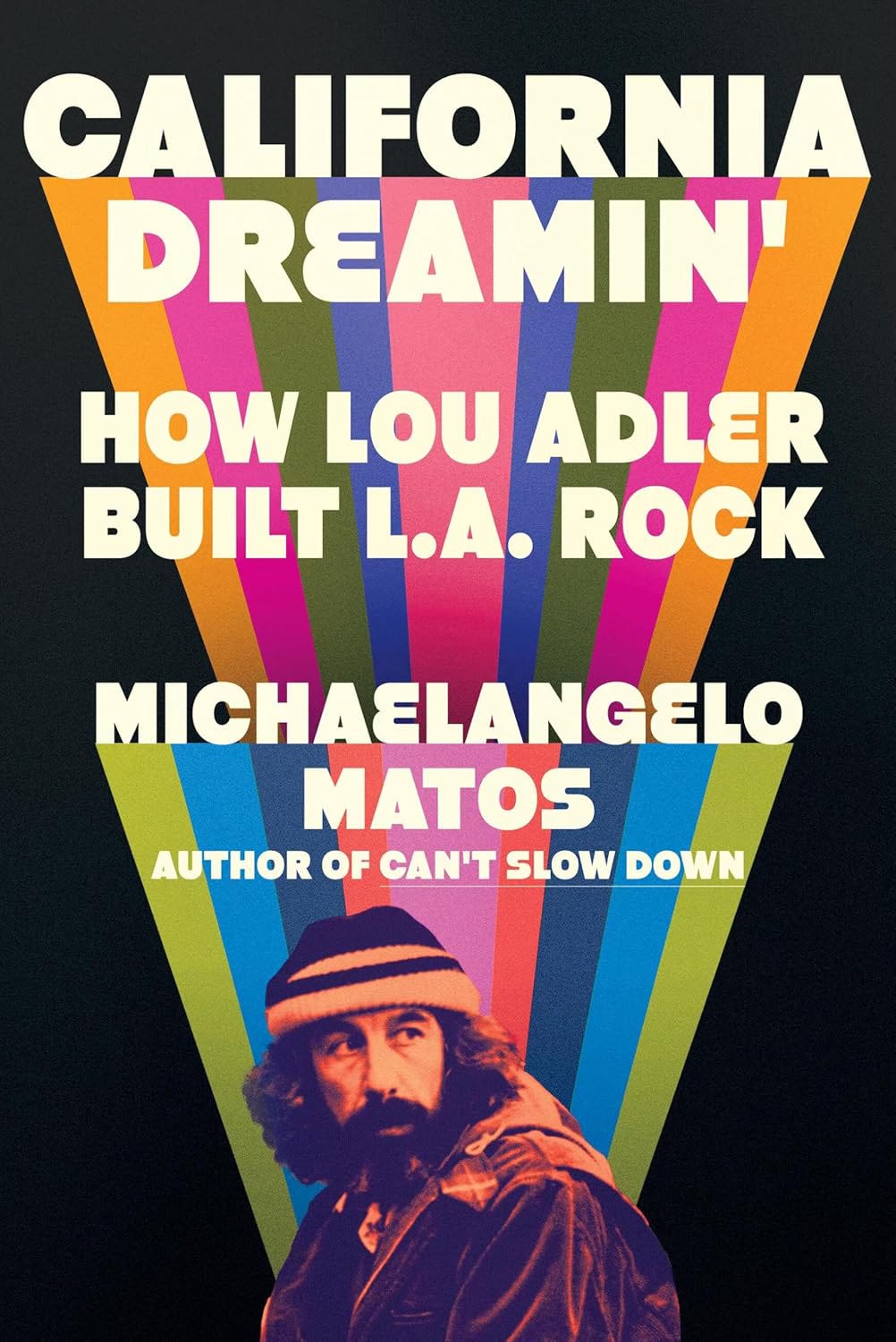

Today, we begin a new Q+A series for the Music Book Club newsletter and site with Michaelangelo Matos, author of The Underground Is Massive: How Electronic Dance Music Conquered America, Can’t Slow Down: How 1984 Became Pop’s Blockbuster Year and the forthcoming California Dreamin’: How Lou Adler Built L.A. Rock.

Music Book Club: Are there authors who inspired you to want to write as a kid?

Michaelangelo Matos: There wasn't one particular writer who made me want to. I conceived of myself as a writer very young, and as a journalist specifically after that, before my teens. But the book I remember reading that pushed me into music writing as an avocation is easy: Greil Marcus's Mystery Train, early teens. It wasn’t the first music book I read, just the one that made it look like the very thing I wanted to do, because I wanted to do something that well.

What do you love about editing other people's books? Since a lot of people may not be aware that you do this as well, I'd love to hear some stories about books that you've worked on that you particularly loved doing.

I have always liked editing writers. “Editor” was in my job title from 2003-06, at Seattle Weekly and, briefly, eMusic; and I edited a cover package for Billboard in 2012, which enabled me to write my proposal for The Underground Is Massive at night. The Dey Street editor who bought the book was panicking at the long chapter drafts I showed him, flop-sweating at my calm assurances that I'd be chopping it to size at the end. When I did just that—cut it first from 375k words to 150k in under two weeks, then down to 125k in four days—he was floored. It was simple: I had written everything I wanted to write. Now that my ego had been satisfied, my job was to turn it into a book, so I did.

A few weeks after TUIM was finalized, I was at a West Village bookstore when Ben Schafer, then (and now) at Da Capo Press, called. Bob Mehr's Replacements book was still unfinished, and it was long. Would I have a crack at it? The pay wasn't good (and was subsequently negotiated upward), but since I had replaced Bob at Seattle Weekly semi-against his will (this was on the company, not either of us), I figured this would help make good, as well as getting to work on something I could potentially add to. (For starters, I'm from Richfield, the suburb where Paul Westerberg went to high school.) Especially having chopped my own book to size, I figured I could do it. And I could—for two solid months. I thought it would be a breeze, and it wasn’t, mainly because Bob didn’t just write long—he’d stuffed the manuscript with telling details. It was long because there was so much there.

I took two passes at Bob’s manuscript. The first time, I just made cuts where and when I saw they needed making. I figured that would be enough. When I looked at it again, I’d only cut about half of what needed to go. (And again, he wasn’t finished writing it yet. What I got was missing a couple of chapters covering—oh, irony!—1984, and the post-breakup/reunion outro.)

So, I did exactly what I had done with TUIM: math. This is where you take ego completely out of the equation. Each chapter had a word count, as did each section of those chapters. X percent of the words still there needed to go. Therefore, my job was to cut X percent of each chapter and/or section. I spent an entire day making a list of how many words per section had to be cut out of Bob’s book, and over the next couple weeks, I cut as many per section as seemed mete.

Sometimes I cut exactly what was called for. Sometimes I cut twice that much, because (for example) once Thing A is gone, you therefore cut all subsequent mentions of Thing A—or whatever. And those numbers always roll(ed) over. If you wound up cutting a 900-word passage down to 500, when you’d expected it to stand at 700, another section can subsequently have 200 words more than projected. And sometimes a section is so strong at its present length—with Mehr, a pretty frequent occurrence—that you cut extra from subsequent sections to keep it intact. I wound up cutting something like 100k words out of Trouble Boys—not as many as Ben or I had wanted to, but Bob hadn’t left us much choice. There was just too much great shit in there.

Ben then asked me to edit another book, Aidan Levy’s Sonny Rollins biography, and shortly after that, his colleague Brant Rumble asked me to edit a third, Bill Janovitz’s Leon Russell biography. The former required much the same methodology as Trouble Boys—just so much amazing detail in there that keeping it intact became part of the remit. (The paragraph on the Chicago drummer Ike Day, on p. 123-24, is one of my favorite pieces of “music writing” ever.) With Janovitz’s book, my first pass took care of so much—I did away with more than one-third of the MS—that a second pass wasn’t necessary. That book, too, is loaded with fascinating detail, but I’d also had a lot of practice by then.

I have also worked on three other books, directly with the authors rather than commissioned by an editor: Philip Freeman’s In the Brewing Luminous: The Life and Music of Cecil Taylor was a breeze, since Phil always writes airtight, and a major learning experience, since I hadn’t heard much Taylor before then. I cut down four chapters in the musicologist Griffin Woodworth’s forthcoming study of Prince’s recordings from Oxford University Press—that was a challenge since you have to allow for the jargon, given the book’s provenance. It’s a landmark piece of work that will have a big effect on how people discuss Prince’s (and others’) music, and I’m excited to have played a part in it.

Ditto Tricia Romano’s The Freaks Came Out to Write. This is what I said, in part, during my introduction of our discussion for the Popular Music Books in Process series: “The week they announced the print paper was ending, Tricia went to New York for a Voice reunion party. She saw people from the paper’s earliest days: Ed Fancher, Jules Feiffer, Jonas Mekas. She called me shortly afterward, and told me, with a kind of alarm and clarity that I recognized in my own moments of realization, that somebody had to write their story, its story, the Voice’s. It had to be her, because she had the idea. I’ll never forget my response: ‘Tricia, if you don’t write this book, I’m going to fly out there and kick your ass.’ I also promised to help, which came in the form of edits, editorial advice, leads on secondary sources, the sorry but stern No that her overabundance of amazing material required.”

Bob’s book is being made into a film. Tricia’s book has been nominated for a National Book Critics Circle Award. Hire me!

Would you like to share any thoughts about your process in writing your next book or anything that has particularly been exciting you with it?

This one has been odd. With TUIM and Can’t Slow Down both, each chapter was its own little kingdom, with a lot of material to synthesize. With this one—a look at the career of Lou Adler, the rock impresario—I had been going through chapter files in isolation, feeling buried under. Only after I began putting a single document together could I see the thing whole—and begin to turn that material into sections.

What advice would you give someone who wants to write a music book?

You have to really need to do it, because there’s no way you will get it done otherwise.

I know it would probably be a difficult ask for you to identify your favorite music books of all time, but I wonder if you could recommend a few recently released ones?

David Browne’s Talkin’ Greenwich Village is both warm and sharp, the story of a neighborhood and its music, focusing on the folk clubs but capturing disco and jazz in its survey, that feels grounded and lived-in. The same is true for Jesse Rifkin’s This Must Be the Place, which covers lower Manhattan to the east as well as west (Browne’s locus), and has even more day-to-day detail about the area and its costs of living over sixty years. Despite their obvious overlap, the books are nothing alike, and are both hugely entertaining and valuable.

You seem to watch a lot of old movies! Would you ever write a film-centric book?

In addition to producing the Everly Brothers, Jan & Dean, Johnny Rivers, the Mamas & the Papas, and Carole King, Lou Adler produced the documentary Monterey Pop, the Robert Altman feature Brewster McCloud, and directed Cheech & Chong’s Up in Smoke, and the punksploitation classic Ladies & Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains. And he produced The Rocky Horror Picture Show. So, I currently am.