Q+A: Cary Baker on His First Book and How Busking Can Help Main Street USA

Interview with a 'writer-turned-music-biz-pro-turned-writer!'

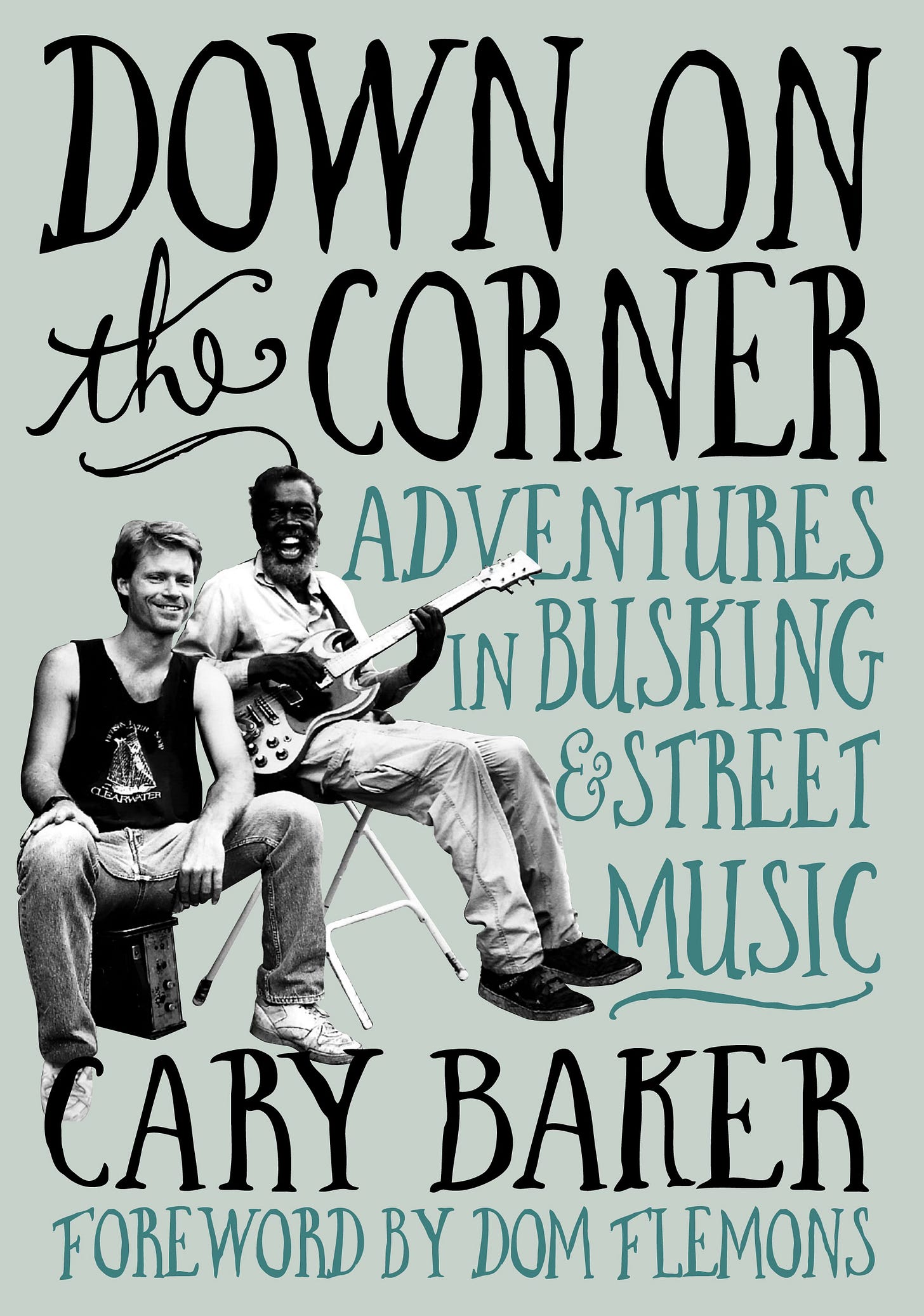

We are happy to share this week’s Q&A with Cary Baker, author of Down On the Corner: Adventures in Busking & Street Music and a self-described “writer-turned-music-biz-pro-turned-writer!”

Tamara Palmer/Music Book Club: What's the life story of your book? How long did you have the idea, and how did you actualize it?

There was a trifecta of influences for the book. The earliest and most profound was this:

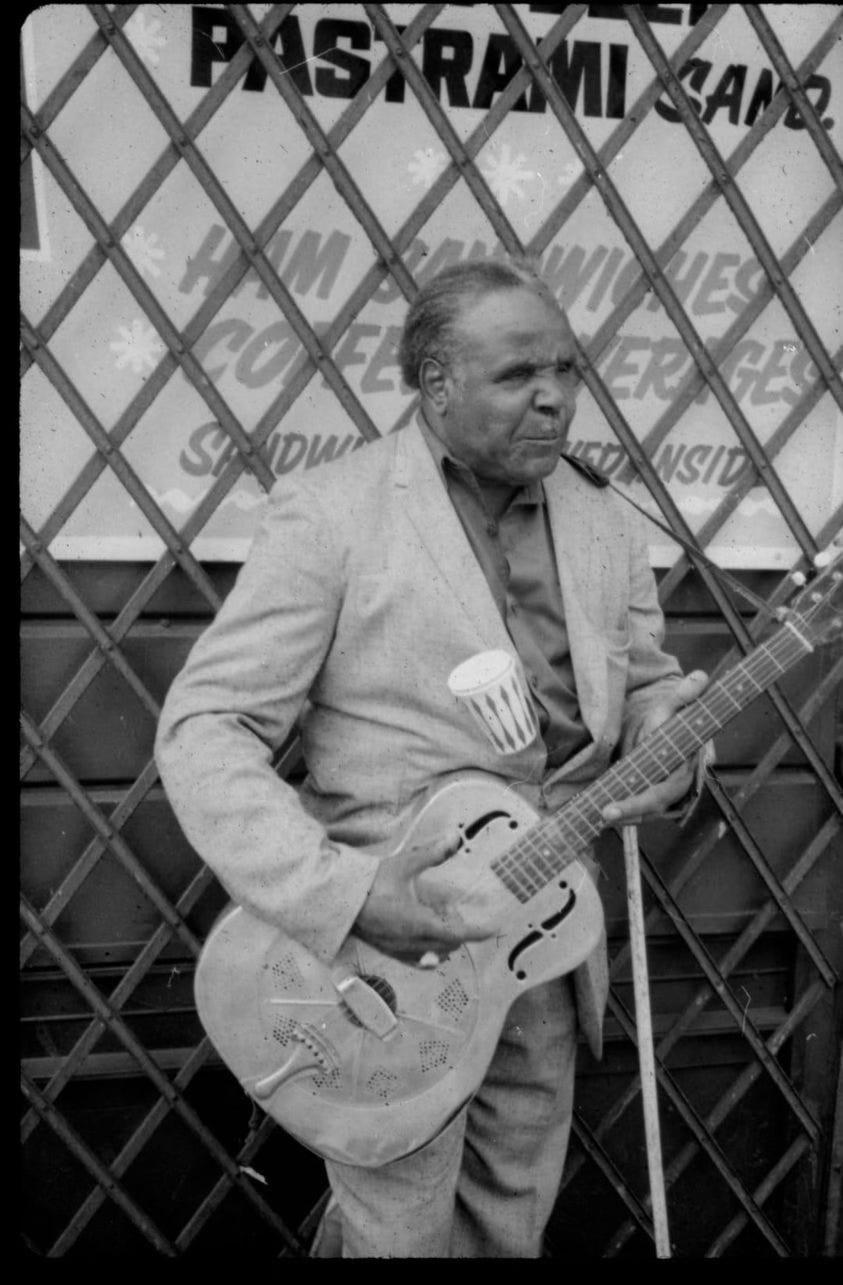

Growing up in the somewhat sheltered Chicago suburbs, my father – son of impoverished Eastern European Jewish immigrants – told me he wanted to take me to Chicago’s Maxwell Street Market, where his parents took him to buy, shop and trade while a child. In the years that had ensued, Maxwell Street morphed from Jewish to Black. One could see the likes of blues legends Muddy Waters, Chuck Berry, Little Walter and Robert Nighthawk on a typical Sunday morning in the late 1940s. By the time I was taken there in 1972, we parked the car across Roosevelt Road at the UIC campus and I immediately heard slide guitar – metal slide on a steel resonator guitar – wafting from many city blocks away. We followed the music and found Blind Arvella Gray performing the folk standard work song “John Henry.” He played it endlessly. But during a break, I introduced myself and got his phone number. I called him and did an interview, which I sent on spec to the fledgling Chicago Reader. The Reader published it, and even sent me a check, which I hadn’t expected. It was the start of my writing career.

Blind Arvella Gray at Chicago’s Maxwell Street Market “on the day I first saw him, 1971 or ‘72” (photo by Cary Baker)

There were two other early brushes with street music:

Cut to 1982, and I was writing for the new wave magazine Trouser Press. The editor called me one day and asked if Milwaukee is anywhere near Chicago. Uhm, yes, why? Apparently there was a punk band in Milwaukee playing on acoustic instruments. And by the way, they were street singers, and were discovered playing outside the city’s Oriental Theater marquee on the city’s streets by Chrissie Hynde and James Honeyman-Scott, who asked the [Violent] Femmes to open for the Pretenders, ahead of their real touring opening act. An introduction to Warner Bros. by the Pretenders helped bring about the Femmes’ Slash contract.

And finally, two years later in 1984, I’d moved to Los Angeles and took my first Venice Boardwalk beach walk on a Saturday morning, I was walking and taking in the scenery – very unlike that of Chicago – when I heard a voice not unlike that of Otis Redding. I looked, and it was an older Black man with white hair and a white beard. I would soon learn that his name was Ted Hawkins, and that he’d lived a hard life during which he’d been imprisoned and institutionalized. But his salvation was music. And his salvation was our gift. Hawkins was eventually signed to a one-album deal with Geffen by A&R exec and producer Tony Berg, who’d been tipped off to Hawkins by friend Michael Penn. Penn had seen him on 3rd Street Promenade, not Venice. But busking was his occupation.

Also in Venice during my first stroll, I witnessed Harry Perry, sikh-robed with a turban, kneepads and rollerskates, with an electric guitar and battery-operated amp. It was then that I knew I’d arrived in La La Land. It turns out Perry was one of the activists on behalf of busking.

By then, I’d also been to New Orleans, of course, and taken a New York subway or two and strolled through Washington Square and Gramercy Park – taking note of buskers at every turn.

How did your research expand your knowledge of music and busking? Were there any big surprises along the way?

For one I quickly discovered that a very good book about busking had been published in 1981, titled The Buskers. It traces the idiom back to outdoor performances in ancient Greece and Rome, noting early American buskers like Benjamin Franklin and working its way up to and beyond the New York folk scene and the tangled web of politics in its eventual legalization.

My book unofficially begins around 1920 with Blind Lemon Jefferson playing in Dallas’ Deep Ellum, along with other blues street singers, working its way into doo-wop, the Greenwich village folk, New Orleans’ centuries-old street music history, and an array of latter-day buskers and street singers. In speaking with more than 100 sources, I heard many tales of city council meetings, changing municipal ordinances, advocates (notably an attorney in New Orleans) who helped busking achieve legality and even desirability, even a foundation (Playing for Change) that helped put a positive focus on buskers while raising funds for worthy causes.

One story that comes to mind when I think back on my interviewing and research process is the story of Fantastic Negrito, né Xavier Amin Dphrepaulezz, who began his career as Xavier on Interscope Records in the mid-‘90s, sounding just a bit like Prince. Everyone who records for Interscope becomes a star, right – Dre, Snoop, No Doubt? Well not Xavier. On being dropped from the label, he retreated to Oakland, became a pot farmer, and began to play on the city streets in search of purpose – keeping his musical muscle flexed. So busking for him as a mid-career, not pre-career, maneuver. In playing the Oakland streets, he discovered it wasn’t Xavier the R&B singer at all, but rather Fantastic Negrito – with music a but closer to folk or blues, or as he called it: "black roots music for everyone." He went on to win Tiny Desk in 2015, and was on his way to Grammys, Blues Music Awards and Americana Honors & Awards.

I also enjoyed talking with Peter Case, who hitchhiked from his native Buffalo to San Francisco, lived in a rusted car in a junkyard, and busked in Fisherman’s Wharf and North Beach – once with Allen Ginsburg joining him outside the City Lights bookstore. He eventually met his first set of bandmates while busking. And once he himself was a Geffen recording artist, he even busked for a group of people who couldn’t get into a sold-out album release show at Club Lingerie in Hollywood. And then he went inside and played to his paying customers.

Mary Lou Lord, who was more famous for playing outside SXSW than any official showcases she may have later secured, reveled me with a tale of a man who peed in her guitar case before stealing the hard-earned money from the case. Her SXSW busks at East 6th Street & Brazos St. drew accompanists like Billy Bragg and the late Elliott Smith.

Another busking oddity: A Nashville street blues singer named Cortelia Clark was discovered by a record producer named Michael Weesner and signed to RCA Nashville – better known at the time for Chet Atkins, Eddy Arnold and Dolly Parton. Because the Grammy Folk category was still under the radar, the label managed to get its voting bloc to get behind Cortelia Clark’s album in the Folk category that year. The competition was steep: real folk legends like Pete Seeger, the Mitchell Trio and Mimi & Richard Farina, as well as bluesman Lead Belly, and – of all things – another blind street singer named Oliver Smith (who rates a chapter in my book as well), who’d had one album on Elektra as Clark had on RCA. Cortelia Clark won the Folk award that year, his album having been recorded on the streets of downtown Nashville. Clark’s health was not great by then and he did not attend the Grammys. He made a few subsequent recordings, yet to be released, before passing. But like Ted Hawkins and Oliver Smith, an example of an artist spotted by the major labels while busking.

I could go on and on – I didn’t even mention Bongo Joe, the San Antonio oil drum banger who recorded for Arhoolie – but I’ll leave this question with one more busking epiphany: Busking helped artists – and audiences – through the pandemic, when concerts were put on hold for six months or more. Jazz singer Madeleine Peyroux – who’d grown up busking in front of French cafés, when her bohemian mother took her to France – talked about how busking the New York streets during the pandemic in search of human connection. And no doubt the audiences were thankful for the experience.

Can I add that busking can help Main Street USA? Now that we can order anything from Amazon – from a book to Magnesium supplement – and it arrives same day or next day, why do we have to go downtown to shop? Perhaps the reason to shop brick and mortar is for community, and part of that community is live music on the street. It can be a solo folkie or an Asheville-style drum circle.

What I do not consider busking – and I’ve seen this a few times lately at Farmers Markets and such – is a smooth jazz guitarist playing to a pre-recorded backing track. I sooner count doo-wop vocal groups in the men’s room of the Brill Building as busking than playing-by-numbers with a rhythm track.

What advice would you give to non-celebrity authors who may essentially need to act as the publicist for their own books, but find that prospect to be intimidating?

Wow, that’s a bit of an inside baseball question, but fair enough: my book is getting pretty good exposure, knock on wood. It’s no secret that after my years as a music journalist from 1972-84, I took what I thought might be a two-year hiatus from writing to accept an offer as head of publicity for I.R.S. Records. It was fabulously exciting working with bands like R.E.M., Fine Young Cannibals and The dB’s. Well, one thing led to another. One label gig led to the next. And 38 years later in 2022, I closed my indie PR shop, Conqueroo, and returned to writing – for love, not money. My primary intention was to write a book. And I was thrilled when Jawbone Press had some interest in my little street music book. I figured the bulk of gaining exposure would fall on me, and I felt I could promote it tastefully, and with a bit of method to my madness given my 38-year PR experience. I also hired a friend and former associate to ride shotgun and work with me on U.S. publicity for a month or two. Jawbone had an indie publicist in U.K. and Europe. So I wasn’t entirely alone in the endeavor. Through well-written-enough pitch notes, I managed to get it featured and/or reviewed on NPR Morning Edition, Chicago Tribune, the Tennessean, Sound Opinions, Variety, No Depression, etc. I offered nearly every chapter as a exclusive excerpts to magazines and online publications that I like. Overall, I am extremely grateful for all the ink spillage devoted to the book.

But to answer your question: Authors – do not try self-marketing at home! Gather the budget to hire a publicist if you can – perhaps your publishing house has one, perhaps not – and preferably one who’s worked music books in the past. It’s a slightly different arc than promoting albums or tours. And it’s a greater life span: Albums are yesterday’s news after a few weeks unless a hit or a tour ensues. But I’m finding – like right now – that one can promote a book that was published six months or more ago. I’m still doing book signing events after two in Los Angeles, plus one apiece in Austin, Memphis, Nashville and Twentynine Palms, with Chicago on the horizon. These signing events have nearly all begun with buskers performing out in front of the bookstore – ranging from a pre-War Delta blues player, a Dixieland band, a blues violinist and an accordionist.

So while the ability to research well and write compellingly remains the most important aspect of nonfiction authorship, the ability to promote is certainly not a minus.

I hear you are presently working on a second book! What can you share about that right now?

I wish I could talk about it but it’s a deeper dive and a longer haul, and won’t be ready til next year. Suffice to say it’s a biography of a musician who’s led nine lives but of whom no one has previously thought to write a biography.

Which music books past or present would you recommend to our open-minded readers?

I had so many influential music books, both as a teenager learning the basics of rock, blues, jazz and folk – and to the present. So a few that randomly come to mind: Nick Tosches and Peter Guralnick were early favorites of mine, and I felt connected to both of them in they both were early subscribers to my high school blues fanzine. 40 years have passed, but you can’t get better than Tosches’ books about Jerry Lee Lewis or Dean Martin or the one with the audacious title Country: The Biggest Music in America, nor Guralnick’s Feel Like Going Home or his books about blues, soul, and Memphis icons Sam Phillips and Colonel Parker.

Let’s add Chet Flippo to that list: His Hank Williams biography was a standout. I consulted Lilian Roxon’s Rock Encyclopedia often – it was my Google before Google. Jumping way ahead, NPR music critic Ann Powers opened doors and broke ceilings with Rock She Wrote: Women Write About Rock, Pop, and Rap. Bay Area author and editor Michael Goldberg gets props for making a book I never thought I’d want to read an absolute page turner: Wicked Game: The True Story of James Calvin Wilsey, the tragic story of Chris Isaak’s lead guitarist. And a few by writers who I’m honored to call friends: Aaron Cohen’s Move On Up, Mark Guarino’s Country & MidWestern, RJ Smith’s Chuck Berry: An American Life, and Bill Kopp’s 415 Records & the Rise of 415 Records. And in terms of a book by someone I had no idea could sustain my interest as a writer, I thoroughly enjoyed Dream Syndicate frontman Steve Wynn’s I Wouldn’t Say It If It Wasn’t True. And then there are books on bands R.E.M., Cheap Trick and Illinois power-poppers Shoes in which I’m quoted. The list goes on and on, and I haven’t scratched the surface of those I’d like to read.

Of course every now and again, it’s good to get out of my wheelhouse and read a novel.

Previously in our Q+A series:

Gina Arnold on The Oxford Handbook of Punk Rock and Working with Academic Publishers

Tom Beaujour on His New Lollapalooza Book and Producing Successful Oral Histories

John Morrison on Boyz II Men and Chronicling Philadelphia Music History

Lyndsey Parker on Writing a 'Stranger Than Fiction' Memoir with Mercy Fontenot

Christina Ward on Running Feral House, a 36-Year-Old Indie Book Company

Ali Smith on Speedball Baby and Telling Stories Without Shame

Arusa Qureshi on Her Love Letter to Women in UK Hip-Hop

Lily Moayeri on Her Favorite Music Books and Writing from a Personal Place

Megan Volpert on Why Alanis Morissette Matters and Writing 15 Books in 18 Years

Mark Swartz on Biggie + Yoko Ono as a Crime-Fighting Duo and Other Fictional Ideas

Annie Zaleski on Cher, Stevie Nicks and Pushing Past Writing Fears

Nelson George on His Next Book and Making Mixtapes in Paper Form

Michaelangelo Matos on Writing and Editing Music Books